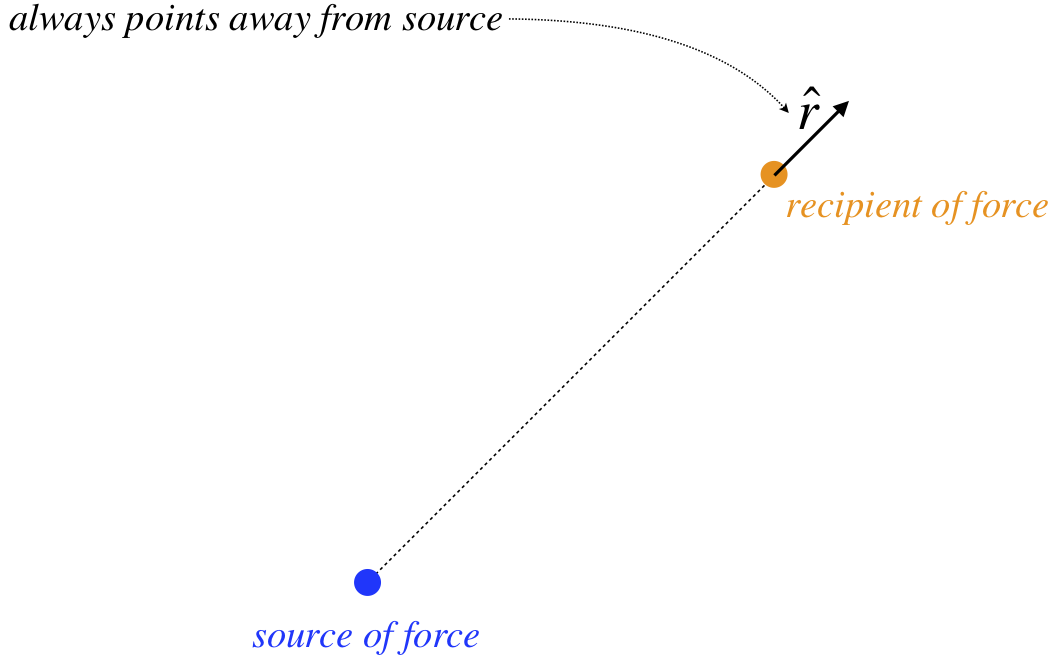

Figure 1.1.1 – Definition of \(\widehat r\)

So given what we know about gravitation, we can explore the action-at-a-distance force we observe with static electricity.

First of all, we know that the static electric force is distinctly different from gravity on two different counts. First, the if we have two neutrally-charged particles, we don't see this amount of force, so it can’t be their masses that are responsible for it. And second, besides an attractive force, we also witness a repulsive force, which we do not see for gravity.

A little playing around with the attractive and repulsive forces shows us that there must be two different types of quantities responsible for the force. Gravity had only one type – mass – but this new electric force must have two different types of “mass,” which we refer to as electric charge . The units for this quantity are named after the fellow who did the first detailed exploration of the force, Coulombs (C) . When we play around with this force, we find that when two of the same kind of charge are brought together, the force is repulsive, while when we bring different types of charge together, the force is attractive. We summarize this phenomenon with the commonly-used maxim:

unlike charges attract, while like charges repel

For now, we can call these two types of charge whatever we like – black and white, left and right, dumb and dumber – anything that distinguishes them from each other. We’ll come back to a convenient description of the two types shortly.

Next we need to explore the other elements of the force, as we did for gravity. Here are the things we find:

Putting these two things together with a constant (similar to \(G\), but with different units) that exists to make our units work out correctly, we end up with a magnitude of the electric force that obeys:

All that is missing is our vector direction, which we covered nicely with the \(-\widehat r\) in the case of gravity. But what do we do here, append a little explanation, “repulsive if both charges are the same type, attractive if they are not?” That is not very satisfying mathematically, and it turns out there is a nice, elegant solution: Call one of the types of charge “positive,” and the other “negative,” and write the force vector as follows:

The \(\widehat r\) means the same as it did before – it points away from the charge causing the force. But notice what our mathematical definition of positive and negative charges accomplishes: If both charges are the same type, then their product is positive, and the force points in the direction of \(\widehat r\), which is repulsive (object is pushed away from the source). But if the charges have opposite signs, then their product is negative, and the force direction is \(-\widehat r\), resulting in an attractive force. The above force law is called Coulomb’s law .

As with any forces, when there is more than one electrical force on a charge, the total force is computed by adding the individual forces like vectors. We call this principle superposition .

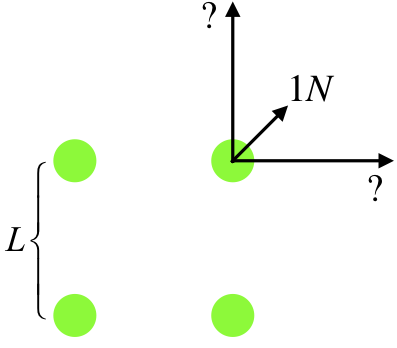

Four identical charges are located at the corners of a square. The force exerted between two charges at opposite corners is \(1N\). Find the magnitude of the net force on one of the charges.

Solution

First of all, with the charges being identical, the force between any pair of charges is repulsive. In the diagram below, we have labeled the length of each side of the square, and drawn in the three forces on one of the charges, one of which is due to the diagonal charge, and the other two are unknown, but they are equal in magnitude to each other, and are greater than \(1.00N\) because the charges are identical and the adjacent charges are closer than the diagonal charge.

Writing the Coulomb force between the diagonal charges in terms of the charges (which we'll call \(Q\)), and the separation (which across a square of side \(L\) is \(\sqrtL\)), we can get the magnitude of the force exerted between adjacent charges, which are separated by a distance \(L\):

Now we superpose the three forces (i.e. add them like vectors) to get the magnitude of the net force, Fortunately this is easy, as the direction of the sum of the vertical and and horizontal force vectors points in the same direction as the diagonal force vector:

There are just a few things we need to say about electric charge before we move on.

This is the amount of charge that resides on the tiny particles we have heard about that reside within atoms: protons (+ charges), and electrons (– charges). We have Benjamin Franklin to "thank" for these sign conventions (we'll see that this choice is a bit of a pain). Despite the fact that charges come in integer numbers, we will treat them as continuous values.

As innocuous as these distinctions may seem, we will see that they lead to some profound properties.

This page titled 1.1: Charges and Static Electric Forces is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Tom Weideman directly on the LibreTexts platform.